Gamera: Always in Godzilla’s Shadow

This is a big one for me! I consider this to be one of my very best. Originally published August 1, 2021, for the 3rd issue of Kaiju Ramen Magazine. This was the first piece I wrote for Kaiju Ramen that started a wonderful partnership.

Below you’ll find the pages from the magazine and the magazine itself if you’d like to read it.

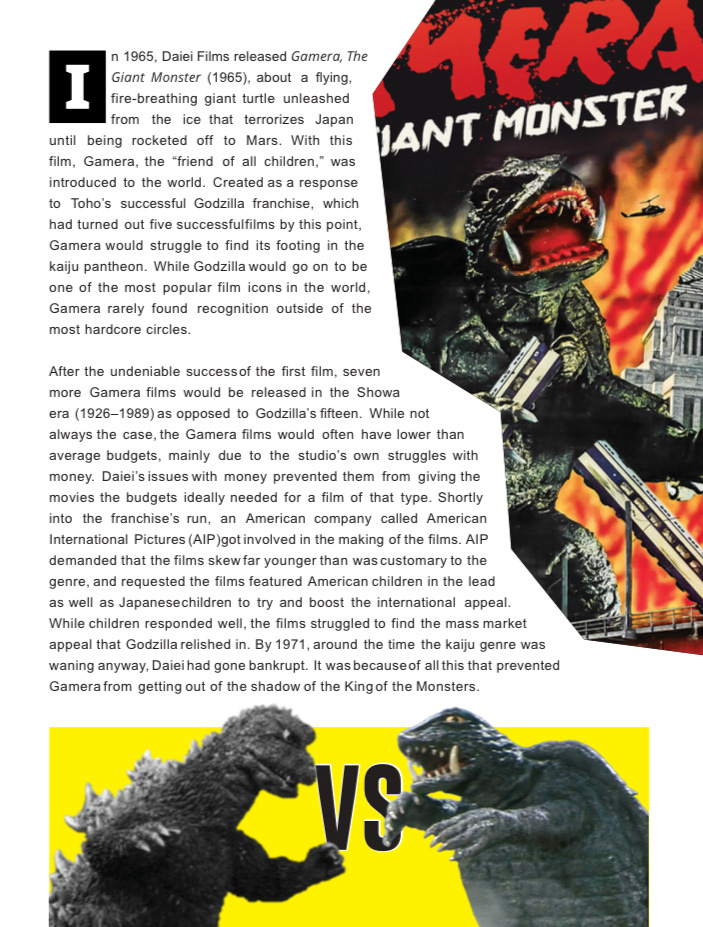

In 1965, Daiei Films released Gamera, The Giant Monster, about a flying, fire-breathing giant turtle unleashed from the ice that terrorizes Japan until being rocketed off to Mars. With this film, Gamera, the “friend of all children,” was introduced to the world. Created as a response to Toho’s successful Godzilla franchise, which had turned out five successful films by this point, Gamera would struggle to find its footing in the kaiju pantheon. While Godzilla would go on to be one of the most popular film icons in the world, Gamera rarely found recognition outside of the most hardcore circles.

After the undeniable success of the first film, seven more Gamera films would be released in the Showa Era (1926–1989) as opposed to Godzilla’s fifteen. While not always the case, the Gamera films often had lower than average budgets, mainly due to the studio’s own struggles with money. Daiei’s issues with money prevented them from giving the movies the budgets ideally needed for a film of this type. Shortly into the franchise's run, an American company called American International Pictures (AIP) got involved in the making of the films. AIP demanded that the films should skew far younger than was customary to the genre. They requested the films feature American children in the lead, as well as Japanese children so as to try to boost the international appeal. While children responded well, the films struggled to find the mass market appeal that Godzilla received. By 1971, around the time the kaiju genre was waning, Daiei had gone bankrupt. All of this prevented Gamera from getting out of the shadow of the King of the Monsters.

Like most competitors, Daiei (now owned by Kadokawa Pictures) was very reactionary to Toho. After Godzilla’s big screen return in 1984, Daiei sought to revive their giant monster. Since the new Godzilla films were finding great success with a darker tone, Daiei felt a similar approach would be necessary for the “friend of all children.” The studio brought on relatively unknown Shusuke Kaneko (director of the the live-action Death Note films) as director, Shinji Higuchi (Co-director of Shin Godzilla) on special effects and Kazunori Itô (Ghost in the Shell) as screenwriter. Together, these three would bring about a trilogy of the most critically acclaimed kaiju films the genre had ever seen. Finally, Gamera, no longer “friend of all children” but rather, the “Guardian of the Universe,” would stand beside the King of the Monsters.

These three films were total reinventions of Gamera and his adversaries, favoring a more serious take over the campy Showa Era tone, while still keeping the giant turtle’s abilities. Like Godzilla, Gamera had something meaningful to say. The reason why Godzilla has had such longevity is because, at the core of the films, they are about something. The original 1954 classic is about post-war Japan with Godzilla acting as a representation of nuclear trauma. Shin Godzilla (2016) is about Japan's ineffectiveness in the face of natural disasters. The original Gamera films, by contrast, weren't about anything meaningful. They were just about a giant monster, fighting another giant monster, while getting some kids involved.

All of that changed during Shusuke Kaneko’s “Gamera Trilogy” in the ‘90s. Now, Gamera had something to say about humanity and the treatment of the Earth. While Gamera was labeled the “Guardian of the Universe,” he was the Earth's guardian. Gamera represented the spirit of the Earth itself. Created to protect the Earth, but not necessarily the people. The more immediate threat was always the monsters such as Gyaos, Legion, or Iris. But, the films were always aware that the people were just as dangerous to the planet.

The financial disappointment of Gamera 3: Revenge of Iris (1999) ended the saga of Gamera once again. While critics hailed the film as one of the best of the genre, the ending left audiences cold, and so, Gamera was put on ice once again. Godzilla made its way to America, and then back to Japan, while Kadokawa struggled one last time to bring their giant turtle to the big screen in 2006 with little financial or critical acclaim. At one point, the studio attempted to pitch a versus movie between Gamera and Godzilla, but Toho declined the offer. For Gamera’s 50th anniversary in 2015, Kadokawa commissioned a short proof of concept video to tease the return of the “Guardian of the Universe” version of the character, but to date nothing has come from that.

Godzilla has enjoyed an almost continuous sixty-six year run, with thirty-five films, and multiple shows from America and Japan, and more coming. With only twelve films, Gamera has lingered in Godzilla’s shadow for its entire fifty-five year run. Even the well received Heisei (1989-2019) films have been relegated to cult classics, only spoken of in the most die-hard circles. None of the films had international distribution for years before 2020. Now that Arrow Video has the international distribution rights, audiences everywhere have the opportunity to rediscover Gamera in all his forms.

Perhaps someday Gamera will return to the silver screen. If there was to be a revival of the giant flying turtle, then it would need to be done with the same care and passion that was seen in the ‘90s. A new giant monster renaissance is happening now, primarily led by Godzilla. New comics, movies, and TV shows of established and original monsters are finding the kind of success that they deserve. If history has taught us anything about the kaiju genre, it’s that if Godzilla is doing well, then Gamera won’t be far behind. If that’s the case, then perhaps, this is the time for Gamera to finally step out of the King of the Monsters’ shadow to get the wider audience recognition it has long deserved.

Here are the original magazine pages designed by Travis Alexander & Michael Hamilton